UX Projects

Avid Group Travel

Context

Avid brings together 8-12 strangers around the world that enjoy the same activity, organizes them into a group, and sends them on an adventure with all of the equipment needed for the activity. The company faces various challenges associated with organizing a group of people without direct leadership and communicating the novelty of both the product and registration process. Note: Avid Group Travel is a website I launched in partnership with one other person.

Figure 1: The Avid landing page

Problem

- Discover friction within the sign-up process. Should we discuss the sign-up process on the landing page? Registration is complex because users must complete registration steps not generally associated with a tour.

- Analyze the effectiveness of the landing page to educate customers and set expectations. Uncover if the value proposition and experience being communicated aligns with customer perceptions.

- Determine how a group can best operate without a designated leader.

Methods and tools used

Usability Testing & Interview: The usability test and interview were based on a sample of five previous customers and five potential customers who fall into the target audience but had not heard of the company. Tasks included selecting a trip, identifying the cost of the trip, and signing up for a trip. An interview question was asked after the initial viewing of the landing page, “what does Avid offer?”, to see if there was a difference between past and potential customers understanding. The interview also targeted the needs associated with adventure travel and if travelers perceived the adverse effects of a guide.

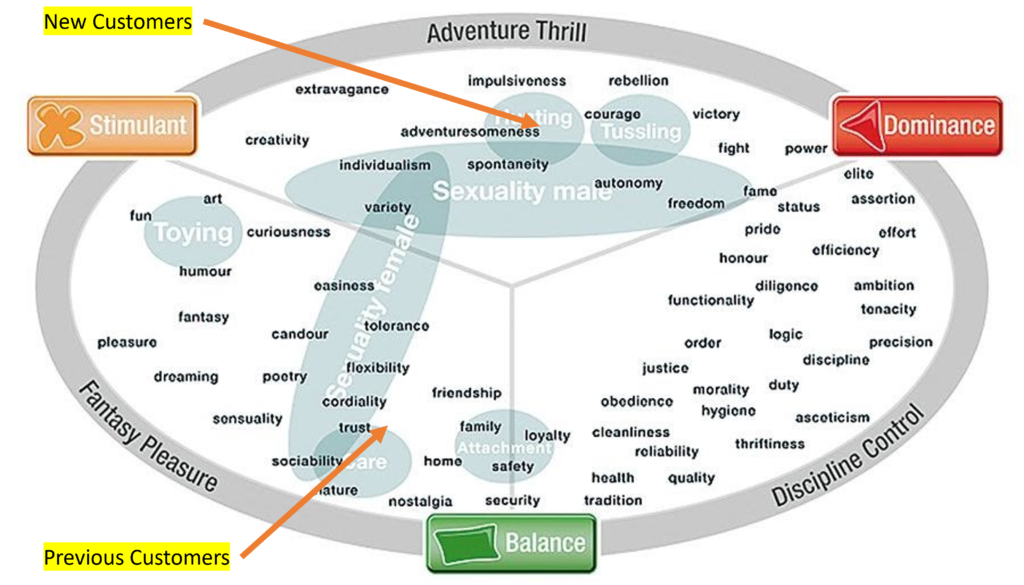

Limbic Mapping: After having spent time on the website, participants were asked to choose words (associated with the limbic map) from a list that they associated with Avid. Results between the two groups were compared, as well as where Avid hopes to position itself as a company.

Results and recommendations

The most important finding from the research was that the group dynamics and shared experience were just as important as the activity itself. The website had initially been communicating adventure and these results indicated that friendship or community should also be marketed. The limbic mapping exercise supported this claim and provided deeper insight into the situation. While new participants tended to associate the Avid experience with adventure and stimulation, previous customers put more emphasis on balance, identifying adjectives like nature and friendship. During the interviews we found that the participants did not have friends willing, or able, to travel with them.

Figure 2: The Limbic Map, originally designed by Hans-Georg Häusel, showing differences in perception

I recommended further study of the adventure vs sociality duality through an A/B test targeting the two motivations in a social media ad campaign. It may be that the latter is learned during the trip and made conscious after the fact, thus rendering it less useful for new customer acquisition.

The results of the usability test indicated various friction points. First, I recommended removing discussion of the sign-up process from the landing page; not only does it confuse customers, speaking of registration does not add to the value proposition, the main goal of this valuable space. Instead, consider educating consumers on this process once they have already committed to signing up.

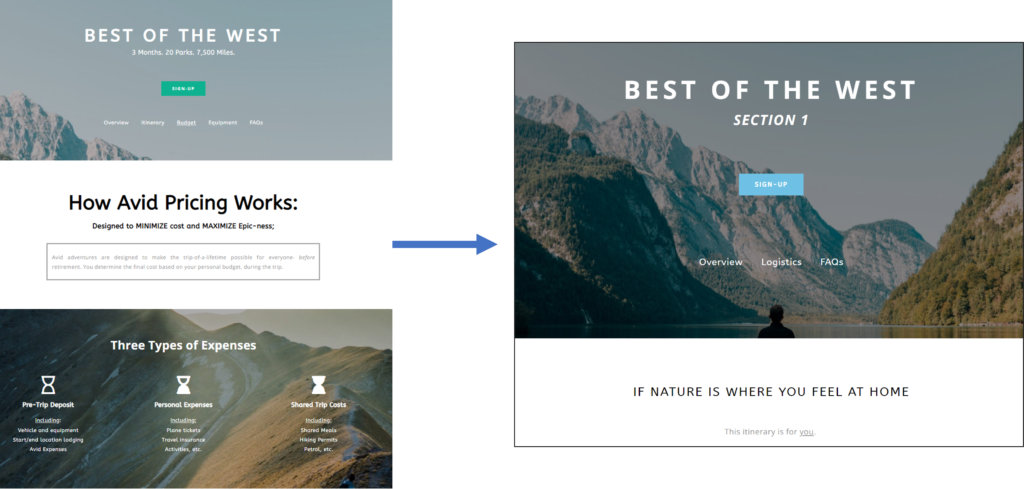

Finally, there was a theme of information overload when users were tasked with signing up for a trip. Having information about budget, equipment, and FAQs might be important, but I recommend making it accessible later in the customer journey. When the customer clicks on a trip, the page should inspire emotion, interest, and excitement- not an aversion to the page caused by “too much reading”.

Figure 3: Removal of information and streamline of the Trip page design

What I would do differently

It would have been valuable to see if Avid could target the sociality/friendship motivation in new customers who were searching for an avdenture-based trip. It also would have been ideal to have someone else run the usability test/interviews, since as a co-founder I was heavily biased towards the company and concept.

Bean-Seed Exportation to Costa Rica

Context

Farmers in Idaho export high quality and genetically modified bean seed. The Idaho Bean Commission (IBC) organizes suppliers under a single umbrella entity to streamline quality and coordinate expansion efforts; the IBC wished to expand operations to Costa Rica. A team was organized to research the opportunity. As the only Spanish speaker on the team, I focused on qualitative research.

Figure 1: Various legumes grown in Costa Rica

Problem

The IBC’s main challenge was the price of their product, which was often three times the price of the standard seeds being used. It was, however, drought and disease resistant while also providing larger yields. Besides convincing farmers to switch to the “modern” seed, the product also had to meet consumer expectations, pass government inspection, and motivate key intermediaries like Walmart.

Methods and tools used

I had four months to prepare for the two-week visit in Costa Rica. I prepared questions for the various stakeholders and identified current pains and potential gains. I also studied the different types of beans along with their cultural relevance. I hypothesized that Costa Ricans would be hesitant to having their livelihood become dependent on a US company. Such a major change to the status-quo often occurs inter-generationally, when competitive pressure forces the issue, which was not yet the case in Costa Rica.

Once in country, we observed how customers used the product as well as interviewing them to better understand price elasticity and how much variability was acceptable in the texture/flavor of the product. We investigated why end consumers chose specific brands and opinions towards genetically modified products.

We understood the challenges farmers would have before arriving. The goal of the onsite visit was to discover which benefits should be communicated to best demonstrate the increased value. We discussed yields and inquired into the relationship between the farmer and intermediaries. We also looked into how often crops are lost to disease and the social systems in place to protect income in such an event.

Figure 2: Visiting farmers in Costa Rica

Results and recommendations

There were two main findings:

First, intermediaries have the most influence in the supply chain. If they demand that farmers use certain seeds, it is likely to happen. Fortunately for the project, these intermediaries also value a stable supply chain- thus our value proposition of draught and disease resistant seeds was appealing. Our team recommended partnerships with key intermediaries who held sufficient power to support our goal. While farmers would be hesitant to change, the increased yields would sufficiently offset the price increase in most cases.

Figure 3: A typical Walmart in Latin America- Walmart has about 300 locations in Costa Rica

The intermediaries, however, would likely not be willing to sell the IBC’s current product. Upon discussing and sharing our beans with various customers and intermediaries, the feedback was clear: this bean is not the same. Therefore, the IBC must align its offering with local tastes before initiating the plan, taking into consideration the cooking temperatures and food storage practices in the region (non refrigerated, open to air, reheated various times).

After modifying the bean seed, the IBC successfully started selling in Walmart throughout Costa Rica.

What I would do differently

This project was undertaken at a moment in life when I was not yet proficient in interviewing, Spanish, or cultural awareness- there were many aspects that could have been improved.

For one, the interviews lacked consistency. I did not ask the same questions to all farmers. Instead, I chose certain questions from the list. Later, we were not able to compare the answers between farmers because there were gaps in the data. Additionally, I wasn’t able to easily relate with the people I was studying. I’m confident that the participants would feel more at ease speaking with me today.

Academic work

Eco Cart – Sustainable Online Shopping

Context

Sustainable consumption is a hot topic. Everyone believes it is the right thing to do, yet the movement has had trouble taking off. One problem identified by consumer research is the distance between consumers and the supply chain- people can’t see the effects of their decisions. With shopping headed online, I feared this effect could grow in magnitude and thus wanted to create a solution to address it.

This project aims to encourage and enable people to shop online both ethically and ecologically. It responds to a global concern regarding the impact of humankind, guiding people to take a second more of their time to consider the effects of their online purchases.

Problem

Of course, modifying online behavior is no simple task. My first objective was to identify who is primarily shopping online in the Swiss market. I attempted to better understand their values and perspectives on ecological products. Finally, I had to determine how to best influence the identified target audience.

Another large component of the project was how to make such a tool enticing to large online retailers and supermarket chains. I needed to design a tool that supermarkets would consider implementing. This constrained the design to not interfering with existing revenue (ideally improving it) and being relatively easy to integrate into existing websites and databases.

Methods and tools used

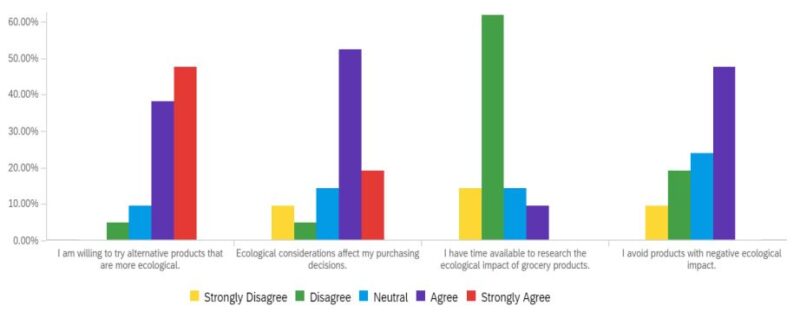

The first method used was a survey designed in Qualtrics. The survey reached about 50 respondents. From the survey, I defined the problem and conducted various interviews to better understand the key users (working parents, tech-savvy consumers, etc).I found that of those people interested in acting sustainably, many didn’t have the time or budget to do so.

Figure 1: Survey questions and results to help define the problem space

Next, I mapped the customer journey, looked at key touch points, and developed personas for members of the target audience. The key differentiating factors between customers were open-mindedness, values towards sustainability, budget, and technological literacy. The key touchpoints along the customer journey were opting into the program, item selection, and checkout.

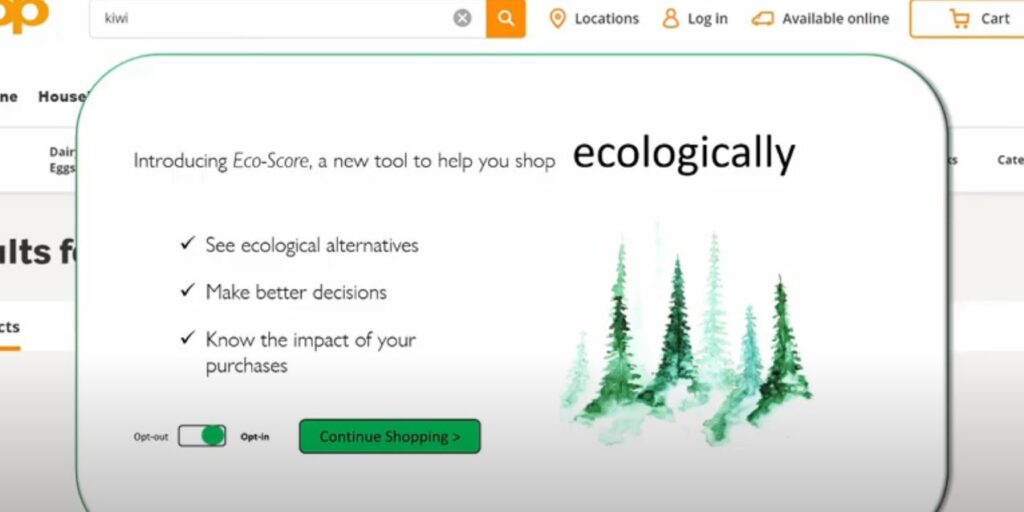

Finally, after designing a very basic prototype, I ran two A/B tests. First, I needed to determine which opt-in screen had the highest conversion rate. Second, I wanted to try and demonstrate that the tool led to more ecological decisions.

Results and recommendations

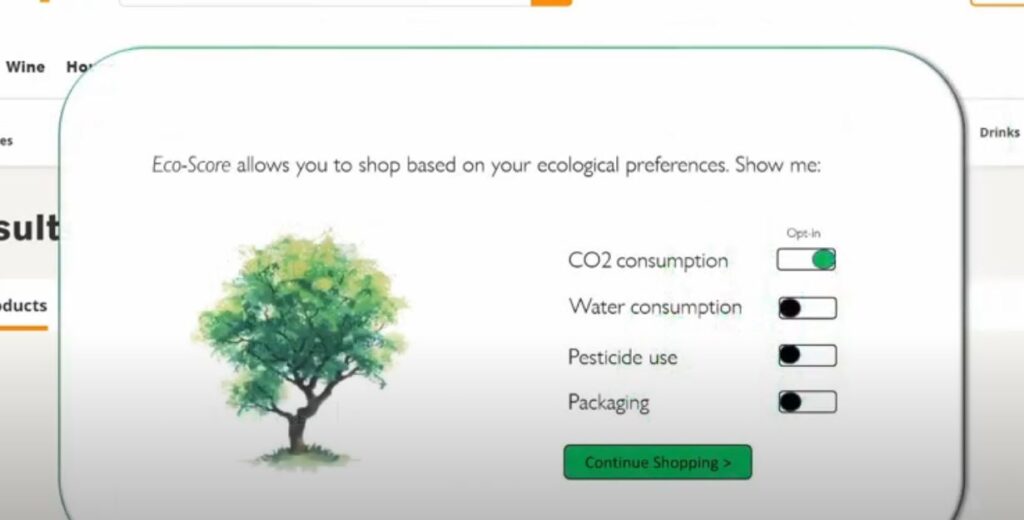

After looking at the A/B test results, it was clear that the streamlined opt-in was most effective in terms of conversion. After opting-in, customers are asked to personalize the experience, inspiring engagement and giving more weight to the proposed recommendations. To pilot the study, I recommended that online stores implement a hook when customers add sustainable products to their basket, indicating that they already hold the “sustainability” or “health” value.

Figure 2: Opt-in screen one

Figure 3: Follow-up screen after successful opt-in

I found that the least invasive design could also be quite effective. By simply making the color of the shopping cart more red or green to indicate the sustainability of a product, I could create a feeling of guilt or anxiety in customers selecting unsustainable products. A slight amount of motion was necessary to ensure attention was brought to the change. However, this feeling wasn’t enough to change behavior in itself, a second step was necessary. When a very unsustainable product was selected, an alternative was offered. This alternative provided an immediate solution to the negative feelings associated with the previous selection. Furthermore, it provided supermarkets with an opportunity to upsell ecological products at the request of their customers.

The results of the A/B test showed that participants were 36% more likely to select an ecological product when the tool was applied. This number varied with budget, though a T-test showed that it was not statistically significant (M = 49%, SD = 14%; t(27) = -.192, P < .10). Post-test interviews also confirmed that certain products or brands were “household favorites” and thus much less likely to be substituted.

Figure 5: Eco-Cart promotional video

What I would do differently

I would certainly improve the audio of the promotional video.

In addition, the A/B testing would need to have a larger sample size to demonstrate the real effectiveness of the tool. I was aware of this when designing the test, but wanted to familiarize myself with the method and applied it anyway. Mechanical Turks would have been one way of increasing the number of participants.

Finally, optimizing for opt-in conversions may not have been the best target. In the end, engagement after opt-in is what counts most. For example, displaying more information on the opt-in screen may have reduced conversion while also significantly boosting engagement with the tool- a balancing act I did not consider.

The Unfortunate Effects of Cognitive Relativism

Context

Humans are cognitively relative creatures. Every judgement we make and action we take is dependent on, or relative to, our current emotional/physiological state, external environment, past experiences, and largely relativistic sensory inputs. Could our biological operating system, based on this relativistic tendency that incites habituation, be impeding sustainable consumption? The goal of the paper is to demonstrate how this fundamental characteristic of cognition is detrimental to a future where consumers act sustainably.

Research Plan

(1) I first reviewed literature regarding relativism in cognition. Various fields point to this conclusion. Experientially speaking, it is quite easy to demonstrate at the sensory level: move your hand from a 0-degree bowl of water to another one containing 5-degree and that near freezing temperature will feel warm! Behavioral Economics also supports the conclusion with Prospect Theory and Salience Theory. In Consumer Behavior research, a large body of work has looked at the effects of mood and emotions on consumption. In general, when we have positive affect, we buy more. In part one of the paper I review and summarize the various theories to support the idea of cognitive relativism.

(2) I then propose various situations in which such an operating system impedes sustainable consumption. For example, comparing ourselves to others doing less, becoming habituated with the status quo (reference point dependence), discounting future costs to the present self, and other perspectives.

(3) I then attempt to empirically demonstrate one of these cases. I do so by priming half of the subjects in a random study to think on an absolute scale before beginning a hypothetical consumption experience, as well as considering their emotional state. Consumer Research has shown that bringing attention to mood and emotions reduces their influence on behavior. The study is conducted on Mechanical Turks, where a significant sample size is easily achieved.

Results

The research phase is still in progress and will be completed by June 2022!